A report by Ed Pybus for Crow Consulting, on behalf of The Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust and the crofters of Eigg. The project was supported by Highland Council’s Community Regeneration Fund.

Introduction

This project, and report, began when the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust (IEHT) wanted to look at how best to support crofting on Eigg. From the initial meeting onwards, crofters have led this project.

The report aims to provide an overview of crofting on Eigg – to help tell Eigg’s story and to increase understanding of crofting within the IEHT and the wider community. This report does not aim to explain the system in detail but seeks to provide a brief overview of key aspects of crofting.

The report also highlights the challenges crofters face, and explores ideas for strengthening and growing crofting on the island. Many of these ideas may also be relevant to other crofting communities across the North and West of Scotland as they plan for the future.

Throughout the project, it has become clear that the challenges faced by crofters on Eigg are also seen across crofting communities in Scotland. These challenges are numerous, interconnected, and pose risks to the realisation of the benefits of crofting. At worst, they could lead to the gradual disappearance of crofting. Across Scotland, we must ensure we are not sleepwalking into economic clearances of crofting areas.

“Crofting has the potential to be the low-carbon model of living that we need more of, combining the production of food, fuel, and energy with economic activity.”[1]

Fortunately, Eigg has a community and a landlord committed to supporting crofting. However, for crofting to truly thrive, systemic change is needed at the national level. This change is vital not only for Eigg, but for Scotland as a whole. Crofting should not be viewed as a fringe activity but as a central part of Scotland’s strategy to achieve a just transition, to become a Good Food Nation[2], to retain rural populations, and to build community wealth and a wellbeing economy.

This report is not the final point, but a step on the way. The process of creating this report has already led to some positive outcomes – a better understanding of crofting, a sharing of ideas and challenges and the first steps towards creating a new grazings committee.

In this report I have tried to distil down six months of conversation, research and observations. A huge thanks to everyone who has given time and shared their stories, the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust board members who have supported this project and most of all the crofters of Eigg. I hope I have accurately reflected the issues they face and offered some solutions. And of course, for any errors in the report, I take full responsibility.

Ed Pybus

January 2025

Summary

Crofting on Eigg

Eigg is a special place for many people both in Scotland, and further afield. Its varied history of ownership, which finally resulted in it being one of the first communities to fund and achieve a community buyout, means it has inspired many other communities across Scotland, who have looked to Eigg as a model. Since 1997 the island has been owned and managed by The Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust.

Crofting is an equally special form of land tenure, with a similar history of struggle. Prior to crofting legislation many small-scale tenants had very few legal rights and could be easily evicted. After years of agitation, hardship, and a Royal Commission, greater protections were given to crofting tenants by the 1886 Crofters (Scotland) Act. These hard-won protections enabled crofters to feel secure on their land, and allowed them to invest in improvements.

Crofting has a long history on Eigg. Crofts were typically of insufficient size or fertility to sustain a family, ensuring the crofter was also available as labour for the landlords needs. Crofts were created on Eigg in 1810 to ensure the landlord had sufficient labour for the harvesting and processing of kelp, which was highly profitable for the landlord. Since then there have been many reorganisations of crofting, the most recent in 2004 when the trust created four new crofts.

There are currently 22 crofts on Eigg, split into two townships: Cuagach and Cleadale. The total area of land currently under crofting tenure is approximately 300ha, around 1/10 of the island. 16 crofts are owned by IEHT and tenanted, 6 are owned by the tenants. None of the crofts are vacant. In total there are 19 tenants some of whom tenant or own multiple crofts. Five crofters are currently absent. There are two common grazing in Eigg, one for the Cuagach crofts and one for the Cleadale crofts. The Cuagach common grazings are approximately 64 hectares. The Cleadale common grazing are approximately 79 hectares.

Crofts on Eigg have a long history of growing food and fodder. Today, many crofters grow small amounts of food, with some growing enough to be self-sufficient in fresh produce. Keeping livestock has always been central to crofting on Eigg. Historically, crofters were only allowed to keep cattle and horses. While this restriction no longer applies, there remains a tradition among crofters of raising cattle rather than sheep on the island.

At present a minority of crofters keep livestock on their crofts. Livestock need to be taken to Mull to be slaughtered, creating additional costs, transport problems and potentially causing animals distress.

Historical photos from the late 19th century show very few trees in Cleadale and Cuagach, aside from those on the farms at Laig and Howlin and the hazel woodlands at the cliff’s base. This was a result of land management decisions made by crofters and landlords over the previous generations. In recent decades, some crofters have been planting trees as an integral part of their land management.

Opportunities and Challenges for Eigg’s crofters

The vision for crofting on Eigg is one that shows that crofting is a viable business, that attracts young people to stay, return, or move to Eigg. This vision includes a mix of businesses, with sustainable food production at its core. Tourism and other businesses have an important contribution to make. It is a vision where all crofts are being used, where each croft retains its independence, but where there are more opportunities for working in community. And it is one where the whole township manages the land sustainably to ensure it remains both productive and supports biodiversity.

Throughout this project, many innovative and exciting ideas have been discussed. To create a crofting plan designed by and for the crofters, I asked them about their vision for both their own crofts and the wider community. As part of the process of developing this report, I spoke to 17 out of the 19 tenants. I also gathered input from external stakeholders. This report highlights ideas that come from discussions with crofters, both individually and in groups. It also includes input from the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, as well as insights from other stakeholders and examples from other communities.

Several common threads emerged:

Food Production

Crofting has always been primarily about food production. As we look for more sustainable ways to grow food and adapt to the effects of climate change, small-scale local food production will be essential. Crofting is uniquely positioned to play a vital role in this future. However, crofting on Eigg faces significant barriers to achieving this.

One key barrier is the slaughter and processing of livestock. There is currently no viable option that allows crofters to directly market their meat, and without this, small scale livestock production on Eigg is financial precarious. In the longer term the barriers to small scale slaughter facilities need to be addressed, and in the short term there needs to be a way for small scale meat producers to get their products directly to market.

For small scale horticulture to be viable, there needs to be investment in the infrastructure needed, and changes to funding that will allow small producers to compete.

Land Management

Crofters feel a strong responsibility to care for the land. They want to balance the needs of both the crofter and the land, ensuring it remains productive. Crofters have a deep connection to the land, whether they can trace their roots back through generations or have more recent ties. Sustainable land management includes both the sustainable grazing of animals and the planting of trees. The successful development of crofting on Eigg will balance these two priorities to meet the needs of the crofting community as a whole.

Fairer Funding

Like all businesses, there is a wide range of support available for crofters, however crofting has specific needs, and the funding systems that are available are often complex and bureaucratic and crofting can often lose out. Without clear fair funding available, crofting will be unable to continue to deliver the wide range of social, community and environmental benefits it currently provides. Agricultural funding must put the needs of small scale producers at the centre of policy – recognising that small scale producers are the ones who will enable Scotland to be a sustainable, self-sufficient food producing nation, and that crofting provides vital infrastructure that supports rural communities. The failure to provide sufficient funding for small scale horticulture needs to be addressed, as does the uncertainty around the longer-term changes to agricultural funding.

Better Infrastructure

Crofting cannot achieve its full potential without the infrastructure needed to support croft-based businesses and communities. Many of these issues apply to the wider community on Eigg, and other areas of Scotland, but some gaps have a specific impact on crofting. Housing, transport and access to markets are all key infrastructure that needs to be in place for crofting to thrive.

Working Together

Each crofter has a clear vision for their own croft, and they also recognise that crofting is a communal activity. Working well with the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, as landlord, and the wider Eigg community is important for the success of crofting. This report discussed some ideas for how the community can work together to realise this vision.

Planning for the Future

A vision for crofting must also look to the future. When crofting is seen as a viable way to earn a living, young people are more likely to stay on, or return to, Eigg creating a sustainable community. Planning around succession, developing businesses, sharing skills as well as tourism and volunteering will all play their part.

Climate change

Climate change presents both risks and opportunities for crofting. Some crofters are concerned that efforts to reduce CO2 or changes in land use could impact their current practices. There are worries about the costs of adapting to climate change and how unpredictable weather could affect crops, livestock, and infrastructure. However, crofting also offers a way to help mitigate climate change. Crofting already produces high-quality, sustainable local food with a low environmental impact. As Scotland moves towards a more sustainable food system, crofters will have new opportunities to play a key part in this.

Next Steps

This report explores these issues in detail, drawing on the experiences of Eigg’s crofters to create some key recommendations to help grow and strengthen crofting on Eigg. These specific recommendations focus on the subjects of this report – IEHT and the crofters. However, many of the issues crofters are facing require action from those outwith Eigg, and responsibility for many of these decisions ultimately lies with the Scottish Government and Scottish Ministers.

Throughout this report there are a number of potential calls, either to support some of the proposal in the report, or to make policy changes. I hope this report helps to provide some of the evidence the crofting community, IEHT, and others need to push for the policy changes that are essential to ensure crofting on Eigg, and across Scotland, is better supported.

Full report

Eigg

Eigg has been inhabited since Neolithic times, its fertile soils attracting settlers after the retreat of the last ice sheets. This long history has left a rich archaeological legacy, ‘from bronze age hut-circles and Iron Age forts to a cemetery of Pictish square cairns, a series of early Christian crosses and, finally, the nucleated townships which were cleared in the 19th century to be replaced with the regimented layout of crofts walls to be seen … today[3]’.

Despite not being the largest of the Small Isles, Eigg is the most fertile and historically supported the highest population, with over 500 residents recorded at the turn of the 19th century. Its central role in the Small Isles’ history earned it the nickname “parent island,” and it housed the region’s surgeon, schoolmaster, and its only manse.

In more recent times, Eigg has had a varied history of ownership, chronicled in numerous books[4]. It was under the control of the MacDonalds of Clanranald for centuries before being sold in the early 19th century to a series of wealthy landowners. Eigg gained prominence in the late 1990s as one of the first communities to fund and achieve a community buyout, becoming owned by its residents in 1997.

The Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust (IEHT) owns and manages the island on behalf of its residents. The Trust comprises three members: the Isle of Eigg Residents Association (IERA), The Highland Council, and the Scottish Wildlife Trust (SWT). Representatives from each serve as Directors of the Trust, with Eigg residents forming the majority of the Board. All residents are automatically members of the IERA, which meets monthly to guide IEHT decisions. Although IEHT owns the land, much of it is tenanted, including three farms and 22 crofts.

Eigg’s current population is approximately 115 but increases significantly in spring and summer with thousands of visitors. Most of the island’s population lives in Cleadale in the north, while the main amenities and piers are located in Galmisdale in the south. A single-track road connects the two ends of the island.

The island is serviced by ferries, with four crossings per week in winter and six in summer, requiring a 1.5-hour journey to Mallaig on the mainland. The nearest town, Fort William, is a one-hour car ride or a 1.5-hour train journey from Mallaig, meaning Eigg residents need at least one overnight in order to visit many amenities.

Eigg has a shop, a café, and the Small Isles Medical Practice, which includes a dispensing pharmacy. A doctor visits weekly from Skye, and emergency transfers are conducted by sea or air. The island supports several small businesses, including a brewery partially financed through community shares,a craft shop, bike hire, outdoor activities and a record label.

Eigg is renowned for its geology and wildlife, which have drawn visitors since the 18th century. Its dramatic silhouette results from the same ancient volcanic activity that created its fertile soils and distinctive basaltic landscapes. Features like the natural amphitheater in Cleadale, the plateau cliffs, and the iconic peak of An Sgurr are products of this volcanic past.

The island’s diverse habitats include coastal land, farmland, willow and hazel scrub, native and productive woodland, raised bog, and moorland. Eigg is home to over 200 bird species, 300 bryophytes, and 500 plant species. Its surrounding waters support whales, dolphins, orcas, and other marine life. Unlike much of Scotland, Eigg has no deer but does have a substantial rabbit population due to limited predators, alongside domestic livestock.

Eigg’s natural heritage is recognised with several designations:

- National Scenic Area

- Marine Protected Area (Sea of the Hebrides)

- Special Area of Conservation (Inner Hebrides and the Minches for harbour porpoises)

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest

Eigg’s rich biodiversity and designations underscore its unique natural environment (see Appendix 7 for more details).

Crofting

The oft-repeated description of crofting as “a small piece of land surrounded by red tape” reflects frustrations with its bureaucracy; and whilst the current system brings its challenges, it also protects crofters’ hard-won rights.

Crofting, as a form of land tenure, is unique to the ‘crofting counties’ of Scotland[5]. Prior to crofting legislation many tenants had very few legal rights and could be easily evicted when, for example, landlords looked to increase the revenue they could generate from their land. After years of agitation, hardship, and a Royal Commission, greater protections were given to crofting tenants by the 1886 Crofters (Scotland) Act. These hard-won protections allowed crofters to feel secure on their land, and allowed them to invest in improvements.

Key to crofting are the security of tenure and protection from excessive rent increase, the right to assign the tenancy to a family member and reimbursement for improvements done to the croft.

Crofting legislation also imposes obligations on the crofters, and the landlords. Amongst these the landlord is obliged to ensure crofts are not left vacant, and crofters are obliged to both live on, or near, the croft and to ensure that the croft is not ‘misused or neglected’.

Subsequent legislation has meant that crofters may have the right to assign their croft to non-family members, to ‘de-croft’ parts of their croft and to buy the land from the landlord. Some newly created crofts, particularly those on community owned land, restrict some of these rights.

Croft Housing

Croft housing has also evolved over time. In many cases, the house is on croft land. However, a ‘croft’ house can be on land that has been ‘de-crofted’, i.e. taken out of crofting tenure. This house, and the land it is on, can then be sold, or used as collateral for a mortgage. A crofting tenant often has the right to buy their croft house and garden. This means that in practice many original croft houses are no longer on croft land, and one croft may have several houses on land that was formerly part of the croft. If a croft has no house on it, there may be a presumption in favour of granting planning permission for a house croft[6].

Sub-letting and assigning

All, or part, of a croft can be temporarily sub-let to another person. The crofter must make an application to the crofting commission in order to sub-let the croft. The landlord, or members of the crofting community, can comment on an application to sub-let. The sub-let is usually for a short period of time, but the Crofting Commission has wide discretion.

A crofting tenancy can be permanently assigned to another tenant, this is called an assignation. Again, a crofter must make an application to the crofting commission, who needs to approve the transfer. When a croft is offered for sale, it is usually the tenancy that is being ‘sold’ and will only go ahead if approved by the Crofting Commission. In practice, over 99% of assignations are approved[7].

A crofting tenancy can be permanently assigned to another tenant, this is called an assignation. Again, a crofter must make an application to the crofting commission, who needs to approve the transfer. When a croft is offered for sale, it is usually the tenancy that is being ‘sold’ and will only go ahead if approved by the Crofting Commission. In practice, over 99% of assignations are approved[7].

Crofting on Eigg

Crofting has a long history on Eigg. Crofts were typically of insufficient size or fertility to sustain a family, ensuring the crofter was also available to meet the landlords’ needs for labour. Crofts were created on Eigg in 1810 to ensure the landlord had sufficient labour for the harvesting and processing kelp, which was highly profitable for the landlord.

Originally crofts were created in Cleadale, Glamisdale and Grulin, they were small parcels of land with a share in a ‘common grazings’ where livestock could be grazed. As happened in many crofting communities across Scotland, the crofts at Grulin were cleared in the 1850s. The 1886 Act gave the crofters greater legal protection, so when in the 1880’s the Galmisdale crofters were moved they were able to insist that they were given crofts in a new township, Cuagach, adjacent to Cleadale in the north of the island, and a new common grazings.

There are currently 22 crofts on Eigg, split into two townships Cuagach and Cleadale. The total area of land currently under crofting tenure is approximately 300ha, around 1/10 of the island. 6 crofts are owned and tenanted, the remaining 16 are owned by IEHT and tenanted. None of the crofts are vacant. In total there are 19 tenants some of whom tenant or own multiple crofts. Five crofters are currently absent.

Formal registration of crofts started in 2014. Crofters are not obliged to register their croft with the Crofting Commission, unless they undertake a ‘notifiable event’, but can voluntarily register their croft[8]. Eight of the crofts are currently registered, and the details are available on the Register of Scotland’s Crofting Register[9].

The crofting townships in Eigg have a patchwork of tenant and owned crofts, alongside residents who do not have a croft. In the 1980’s the Lochaber Housing Association built a number of houses and a day care centre (which is now used as volunteer accommodation) on what had previously been croft land. One previous croft house is now managed by Chomunn Eachdraidh Eige (Eigg Historical Society), providing an example of the historic occupancy of the crofts. There are several information boards in the township illustrating the history of crofting on Eigg.

Since the 1880’s, when all the crofters were moved to Cleadale and Cuagach, there have been several re-organisations, that have increased the area of the common grazings and amalgamated some crofts. The most recent reorganisation was done in 2004. This resulted in the creation of 4 new crofts and a new common grazings. At this point IEHT decided that it was appropriate to limited some of the rights that the new crofters would have. This included limiting the right to buy the croft and that the community, via IEHT and the Grazings Committee, should play a role in the assignation of any crofts. This was done via a memorandum of understanding with the incoming tenants, rather than clauses in the lease. The incoming tenant was also required to submit a management plan for the crofts.

In practice the rules around assignations have not been enforced, and has led to concerns being raised about the creation of any additional crofts on Eigg (See Case Study – Croft creation at Kilfinan Community Forest Company for how these conditions can be more rigorously enforced).

Community

Crofting plays a vital role in sustaining small rural communities across Scotland. According to The Value of Crofting[10] report by the Crofting Commission, crofting supports numerous jobs and ensures that ‘80% of the wealth generated by crofting stays within the crofting counties.’ This highlights crofting’s economic importance, both in creating employment and keeping wealth circulating within areas that often face limited job opportunities.

Amongst the crofters there is a strong sense of individuality – each crofter had a clear idea of what they wanted to achieve – but also an understanding that crofting is, at its best, a communal activity and everyone was clear on the need to work together to ensure both their croft, and the township, was successful. There was a feeling that at present there were fewer opportunities for communal activities.

However, this was coupled with an understanding that, even in the absence of organised communal activities, crofters remained ready and willing to lend a helping hand, share tools, or provide supplies as needed.

Livestock

Keeping livestock has always been central to crofting on Eigg. Historically, crofters were only allowed to keep cattle and horses. While this restriction no longer applies, there remains a tradition of raising cattle rather than sheep on the crofts.

At present a minority of crofters keep livestock on their crofts. Livestock need to be taken to Mull to be slaughtered, creating additional costs, transport problems and potentially causing animals distress. One crofter said they wouldn’t send animals to slaughter due to the distress the transport to Mull would cause. Four crofters currently keep cattle, and two keep sheep – one mainly for wool. Cattle are currently raised for meat. These crofters earn some income from their livestock, but it remains economically marginal.

Horticulture

Crofts on Eigg have a long history of growing food and fodder. Today, many crofters grow small amounts of food, with some growing enough to be self-sufficient in fresh produce. However, none currently earn more than a negligible income from selling their produce.

Diverse Businesses

Several small-scale businesses operate successfully from the crofts on Eigg. Some add value to local produce, selling bluebell seeds, willow, and sheep’s wool. Lageorna is a thriving restaurant and bed-and-breakfast run from a croft. Other crofts offer self-catering accommodation or camping facilities. Crofts provide a base for various other businesses such as Selkie Explorers – a sailing business that is run from a croft.

Like most crofts across Scotland, those on Eigg typically meet only part of the crofters’ needs, whether for food or income. Most crofters rely on supplementary income from employment, self-employment, or other sources.

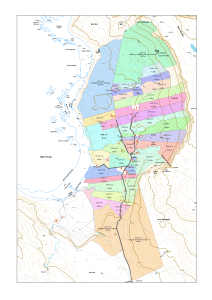

Approximate layout of the crofts on Eigg

Common Grazings on Eigg

There are two common grazings on Eigg: one for the Cuagach crofts and one for the Cleadale crofts. The Cleadale common grazings is split into two sections – the original grazings and new grazings, which were created after the reorganisation in 2004.

The Cuagach common grazings are approximately 64 hectares. The four crofts in Cuagach have shares in the common grazings. The Cuagach common grazings are not currently used for grazing, but they do have a telecoms mast on them. The telecoms company pay rent for the mast, which is split between IEHT and the crofters with shares in Cuagach common grazings. They were previously fenced, but much of the fencing is in a poor state of repair. The common grazings are bisected by the road between Cleadale and Glamisbay. There are no apportionments of the common grazings registered with the crofting commission.

The Cleadale common grazing are approximately 79 hectares. The 18 crofts in Cleadale all have shares in the common grazings. The common grazings are used for the grazing of cattle and sheep. They are fenced, but the fencing needs repairing or replacing in various sections. Sheep from the farms can easily get onto the common grazings. There are two vehicle access points onto the common grazings. There are communal cattle handling facilities that were installed by the grazing committee. Access to the popular beach, the Singing Sands, is across the Cleadale common grazings, either via the road at croft 9, or an access track next to Howlin House; neither access is clearly sign posted. There are two scheduled monuments on the common grazings.

There is one grazing committee that is responsible for managing both townships’ common grazings. In the past a decision was taken to split the common grazings committee, but this was never recognised by the Crofting Commission. The grazings committee has been inactive for a number of years and a new grazings committee need to be appointed. It has previously been active and, for example, applied for grants and maintained the fencing and stock handling equipment. Eigg provides an opportunity to explore how a community landlord and the crofters can work together to productively use the common grazings.

Woodlands and trees

Historical photos from the late 19th century show very few trees in Cleadale and Cuagach, aside from those on the farms at Laig and Howlin and the hazel woodlands (now a Site of Special Scientific Interest[11]) at the cliff’s base. This was a result of land management decisions made by crofters and landlords over the previous generations.

In recent decades, some crofters have been planting trees as an integral part of their land management. For instance, one croft has demonstrated that closely grown copses of native trees can eradicate bracken while significantly enhancing biodiversity—most notably, the increase in bird populations is quite striking. There is considerable natural regeneration in some areas where grazing pressures have been reduced – although in some areas, even where grazing pressure has been reduced, there is limited natural regeneration which could be due to very limited seed banks, or the pressure of rabbits and other animals.

Opportunities and Challenges for Eigg’s crofters

The vision for crofting on Eigg is one that shows crofting is a viable business, that attracts young people to stay, return, or move to Eigg. This vision includes a mix of businesses, with sustainable food production at its core. Tourism and other businesses have an important contribution to make. It is a vision where all crofts are being used, where each croft retains its independence, but where there are more opportunities for working the community. And it is one where the whole township manages the land sustainably to ensure it remains productive and supports biodiversity.

Many innovative ideas have been proposed to develop crofting on Eigg. To create a crofting plan designed by and for the crofters, I asked them about their vision for their own crofts and the wider community. As part of the process of developing this report, I spoke to 17 out of the 19 tenants. I also gathered input from external stakeholders. This section highlights ideas from discussions with crofters, both individually and in groups. It also includes input from Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust (IEHT) and Isle of Eigg Residents Association (IERA), as well as insights from other stakeholders and examples from other communities.

Common Themes

Several common threads emerged:

- Food Production: Crofting has always been primarily about food production. As we look for more sustainable ways to grow food and adapt to the effects of climate change, small-scale local food production will be essential. Crofting is uniquely positioned to play a vital role in this future.

- Land Management: Crofters feel a strong responsibility to care for the land. They want to balance the needs of both the crofter and the land, ensuring it remains productive. Crofters have a deep connection to the land, whether they can trace their roots back through generations or have more recent ties. Land management includes both the sustainable grazing of animals and the planting of trees. The successful development of crofting on Eigg will balance these two priorities to meet the needs of the crofting community as a whole.

- Fairer Funding: Like all businesses, there is a wide range of support available for crofters, but the systems are complex and often crofting can lose out. Without clear fair funding available, crofting will be unable to continue to deliver the wide range of benefits it currently provides.

- Better Infrastructure: Crofting cannot achieve its full potential without the infrastructure needed to support croft-based businesses and communities. Housing, transport and access to markets are all key infrastructure that needs to be in place for crofting to thrive.

- Working Together: Each crofter has a clear vision for their own croft, and they also recognise that crofting is a communal activity. Working well with the IEHT, as landlord, and the wider Eigg community is important for the success of crofting.

- Planning for the Future: A vision for crofting must also look to the future. When crofting is seen as a viable way to earn a living, young people are more likely to stay on, or return to, Eigg creating a sustainable community. Planning around succession, developing businesses, sharing skills as well as tourism and volunteering will all play their part.

Climate Change: Risks and Opportunities

Climate change presents both risks and opportunities for crofting. Some crofters are concerned that efforts to reduce CO2 or changes in land use could impact their current practices. There are worries about the costs of adapting to climate change and how unpredictable weather could affect crops, livestock, and infrastructure.

However, crofting also offers a way to help mitigate climate change. Crofting already produces high-quality, sustainable local food with a low environmental impact. As Scotland moves toward a more sustainable food system, crofters will have new opportunities to play a key part in this. Changes in funding could require carbon audits, which rather than being seen as a burden, could be used to show the low environmental impact of crofting. There are also opportunities for investment and grants that support climate change mitigation and environmental benefits, such as increased biodiversity.

Food production

‘The current food system was developed within the “food as commodity” narrative, seeking to feed the world by any means possible. The result is a food system based on extractive and exploitative practices that are responsible for at least a third of greenhouse gas emissions, and that fail to eradicate hunger and food insecurity’.[12]‘

Crofting has always been primarily about food production. As we look for more sustainable ways to grow food and adapt to the effects of climate change, small-scale local food production will be essential[13]. Crofting is uniquely positioned to play a vital role in this future. Crofters across Scotland use diverse business models to produce a wide range of produce. However, as this report highlights, they also face significant barriers. Alongside other crofting communities, Eigg can demonstrate the vital role small-scale agriculture plays in creating a sustainable food system. While crofting alone cannot resolve Scotland’s food production challenges, it can contribute meaningfully as part of broader systemic changes.

Eigg aspires to become more self-sufficient in food production and to establish an efficient, sustainable circular economy. To achieve this, the island could undertake a study to determine the annual food production required to meet its needs.

The Fruit and Veg Alliance has calculated the volume of fresh produce the UK needs to consume and identified the shortfall between production and consumption. A similar approach could be applied to Eigg by calculating the island’s fresh food consumption requirements. This would provide a meaningful target for local fresh food production, helping to guide efforts toward being more self-sufficient.

Increasing livestock or food production will have an impact on local biodiversity. Careful consideration must be given, not only to observe the limits put in place by regulation, but also to ensure any impacts are minimised. For example, using permaculture design principles[14], regenerative farming[15] ideas and organic standards, systems can be designed that work with, rather than against nature.

Livestock

Some crofters see livestock as a vital part of crofting, others see a role for livestock in their crofts integrated with other land use, whilst others do not see livestock as part of their croft plan.

Traditionally, livestock, along with horticulture, was the main focus of crofting. There is concern, from crofters on Eigg, and the wider crofting community, that unless things change we may be seeing the unintentional end of livestock crofting due to a number of different policy and funding decisions that have been made over the past couple of decades.

At present livestock production is often not financially viable, for example those keeping cattle barely breaking even, and two crofters are considering giving up cattle. This creates difficulty for the future of livestock on Eigg, with new crofters unlikely to take on livestock unless they can see a way for it to be done sustainably.

Small scale livestock production can play a key role in the production of sustainable, high quality animal products, that has high levels of animal welfare. To continue, livestock production needs to be financially viable, as well as environmentally sustainable.

This requires sufficient investment, in individual crofts and in infrastructure, and a level playing field, so small scale producers can compete with large scale producers and small shops and distribution networks can compete with supermarkets.

Most livestock, including poultry, now require registration[16]. The Farm Advisory Service provide a number of general advice sheets on registration of livestock[17] and can provide crofters with specific advice via their advice service[18].

Cattle

The current agricultural funding schemes are focused on providing support for keeping livestock, particularly sheep and cattle, so there are opportunities for crofters to access some financial support for keeping livestock. However, even with this support, cattle are not seen as financially viable at present. Many successfully small-scale livestock producers in Scotland are able to sell their produce directly to consumers – unfortunately, due to the costs and distance to the nearest abattoir, this currently seems unviable on Eigg. Eigg raised organic beef could fetch a premium price, if it could be sold directly to consumers. Having a way to supply customers directly would be a big step towards making cattle, and other livestock, viable on Eigg.

There is also concern that some of the crofters that are keeping livestock are getting older, and this means that the system is not resilient – an accident or illness could mean that there isn’t anyone available to look after the livestock. There are the skills, knowledge and infrastructure on Eigg to keep cattle. So it would be possible for individual crofters to either start keeping cattle, or increase the number of cattle they hold, although looking at ways of working together may provide more sustainable and resilient options.

As well as meat, there is interest in exploring the possibility of a small dairy herd. A larger scale diary such as the Wee Isles Dairy on Gigha may not be viable, but the Highland Good Food Partnership have a podcast[19] exploring setting up micro dairies, showcasing The Sheiling Project that could provide a template for Eigg. This would require an investment, of both time and money, but a small dairy herd could be managed in such a way to ensure peak production coincides with the greater demand that there is during the summer, and excess milk could be made into cheese and other products to supplement the income.

Case Study : Livestock and Horticulture at Knockfarrel Produce

Knockfarrel Produce is run from a 45 acre croft about 5 miles from Dingwall. They started in 2010 and now supply 220 customers with fresh, organic meat, fruit and veg for 44 weeks of the year. 90% of the produce is grown on the croft, the remaining 10% is brought in. Wholesalers act as a backup if needed.

Boxes are delivered to customers every two weeks. Customers are supplied with a standard veg box and can buy in additional produce, including meat. Demand is sufficient that they can replace customers if they leave – giving them some degree of certainty. Customers pay by direct debit, and they use an online payment system to manage the orders (https://www.ooooby.com/).

They grow on a six-year rotation on the outside beds, growing green manures on beds for three years before returning them to productive cropping. They have two planting systems – 5000m2 which is hand planted, and 3ha which are covered in biodegradable weed suppressing mulch and planted by machine. They grow soft fruits and have a 25 acre productive woodland, including a 300 tree apple orchard. Most crops are grown outside, although they do have 600m2 of indoor growing space. They use Keder Greenhouses, strong insulated poly tunnels, after losing four standard poly tunnels in storms.

Much of the produce is stored in the ground, such as brassicas and root crops, and harvested when needed. By protecting crops, and carefully selecting varieties, they can ensure a long cropping season, reducing the need to store produce. They do store some produce, notably potatoes, as they are easier to lift when the ground is dry, which are stored in temperature controlled storage that they rent.

Livestock are also incorporated into the system. They have outdoor reared pigs which are useful in the crop rotation – they will eat left over vegetables and clear deep roots. They have an on-site butchery unit that they use to process approximately 60 pigs per year.

They have experimented with over 600 different plant varieties over the last 15 years and currently grow 180 varieties of 81 different crops. They spent the first five years improving the soil to get it fully productive, using soil amendments, green manures, crop rotation and composting to build up the fertility of the soil. The site is now certified organic. Shelter is an important part of the overall plan, and they have planted over 2km of hedging to provide shelter for the crops.

They have a commercial kitchen on site – which is used for making jams, cordials, apple juice, and cider and during the summer produces a lot of pesto and tomato sauce. These are included as extras to veg box customers. The kitchen is also rented out to other local producers.

Total capital investment is around £120,000 including CCAGS grants and loans. The business supports the equivalent of 5.3 full-time posts. The business is profitable, and they estimate that turnover per Ha has increased from £380 when the crofts were focused on sheep to £16,400 per Ha – although there are now much higher investment and running costs.

Poultry

At present, no crofters keep poultry for more than personal use. Poultry keeping could be a good first step for the production of meat on Eigg for Eigg. The Landworkers Alliance have produced a Setting up a Small-scale Pastured Poultry Enterprise video[20]. Poultry can be slaughtered on the croft and sold, provided the crofter is correctly registered and licensed. The preparation of the birds can be done by hand, but small-scale poultry equipment is also available.One croft had previously supplied a large number of eggs. Egg production, either communally or individually, could play a role in Eigg’s becoming more self-sufficient. Eggs sold direct to the public (e.g. via an honest box) may not require registration or licensing. If eggs are sold via a shop, for example, there needs to be a registered egg packing facility – however, getting this licensed should be relatively straight forward. Highland Council Environmental Health Services can provide more information.

Other livestock

Although cattle have been the focus of large livestock on Eigg, sheep and pigs and other animals such as goats have also been kept in the past, so there is knowledge and experience of working with a range of livestock. These face the same issues and opportunities as cattle – high costs, difficulty transporting to slaughter and low prices but also potential access to funding and grants.

There is also interest in keeping bees. Beekeepers are not required to register, although a voluntary registration system exists across the UK[21]. The Scottish Beekeepers Association (SBA) covers the whole of Scotland, and regional Beekeepers Associations can provide advice and training. Recently there has been an increased interest in ‘Natural Beekeeping[22]’, using a less interventional approach than conventional beekeeping. The Scottish Native Honey Bee Society[23] is keen to promote native Scottish honey bees, believing they are better suited to the damp, cold Scottish conditions. Eigg’s distance from other bee colonies could provide an opportunity to create a native bee reserve, as has been created on the isle of Colonsay.

Working together

There are many opportunities to work together when raising livestock. This could take the approach, that is largely followed at the moment, of individual crofters having their own livestock but looking for ways to work together. However, there are opportunities for a more formal approach.

The first step in working together is the re-establishment of a grazing committee to manage the common grazings.

Managing livestock has traditionally been a communal activity and, due to the small size of crofts, a communal approach to keeping livestock is perhaps the most viable approach. There was interest in exploring a common herd for the crofters.

One option would be the creation of a stock club[24]. This could reduce costs and share risks. These are regularly used for sheep, but could also be used for cattle and in theory could include other communal livestock such as pigs. There are a number of options for the creation of the stock club, from unincorporated association, though to formal partnerships or co-operatives[25]. Crofters interested in a stock club could look at the possible options.

There are also opportunities to work with the three framers on Eigg, sharing skills and knowledge, equipment, reducing transport and veterinary costs as well as potentially, over time, working in a more integrated way. Sandabhor Farm is moving from sheep to cattle, and are exploring regenerative agriculture, becoming certified organic, and using a grazing rotation system to reduce the amount of feed that is brought in. Their experiences could provide useful information for the crofters. There may also be ways for individual crofters, or crofters as a group, to explore working with the farm, for example grazing animals for part of the year on croft land.

Fencing

Concerns were raised about the control of livestock – there was an awareness of the range of damage that different livestock can cause to plants, trees and when grazed on unsuitable land. Having an understanding within the townships about stock control, and a forum for raising any issues, could ensure that any issues are addressed.

Livestock slaughter

Over the past few decades, there has been a reduction in the number of abattoir facilities in Scotland. For many small producers this has led to an increase in the travel times, and the expense, of getting animals slaughtered, and getting produce returned for sale. This is putting a very real pressure on small scale livestock production.

This is exacerbated for island communities, the cost and difficulty of co-ordinating transport can mean meat production is unviable – this seems at odds with both the Scottish Government’s commitments within the Good Food Nation and, when we know that small scale food production is often the most sustainable way of producing food, sustainable food production.

At present the costs, and distress caused by the long distances stock have to travel, means that some crofters on Eigg either see livestock production as unviable, or are unwilling to send animals to slaughter due to animal welfare concerns. When animals do go to slaughter, due to the additional transport costs and logistics, meat does not return to the producers to be sold directly to consumers, which would allow crofters to get a premium price, but sold to buyers.

Much of the production on Eigg is organic, either by design or just due to the high costs of bringing non-organic feed onto the island. However, getting a premium for organic meat is difficult – there needs to be sufficient organic certified cattle at the slaughterhouse at any one time to attract buyers, and as this cannot be guaranteed, the crofters are unlikely to be able to get an organic premium, even if they have got organic certification.

Local slaughter facilities could make a huge difference to the viability of livestock production on Eigg. Investing in butchery and meat processing facilities as well as storage facilities, alongside with slaughter facilities, could provide additional added value[26]. This would reduce both costs and stress to animals, and allow crofters to sell their meat directly to consumers, both on and off the island.

Some abattoirs used to offer a ‘pack and send’ scheme, where they slaughter, butcher, package, and send out meat from the abattoir directly to a crofters customers. This was a very attractive option for crofters on Eigg, as it allowed them to get a higher price for their meat, and generate sufficient income to make keeping livestock viable. Until local meat processing facilities are available to crofters on Eigg this would be a solution. The current lack of such a scheme in Scotland is a major barrier, and addressing this gap must be a priority.

Horticulture

The UK is heavily reliant on imported fruit and vegetables[27], which in the longer term is unsustainable, with many of the countries we import food from facing their own climate-related challenges and sustainability risks[28].

There are barriers to growing more fruit and vegetables, both on Eigg and across the UK. The Fruit and Veg Alliance, an umbrella group representing various organisations, published a report titled “Cultivating Success.” The report outlines what is needed to support fruit and vegetable production in the UK. Many of its recommendations—such as training the next generation of growers, supporting small-scale organic farming, and making it easier for producers to sell their products—are highly relevant to crofting.

Crofting can play a key role in growing fresh produce. Donald Murdie notes in his introduction to Horticulture : a Handbook for Crofters[29], that just a few decades ago most crofters would have been growing fruit and vegetables – there is a long tradition of horticulture on crofts. Traditionally most fodder would also have been grown on the crofts, and with the increased costs of buying in fodder there is an opportunity to grow more fodder for livestock.

Many crofters already grow produce for their own use. The challenge now is moving beyond individual consumption to produce a surplus for sale. This brings additional challenges, such as getting the surplus to market and eventually growing specifically for target markets or outlets. Crofters on Eigg are interested in growing a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, including traditional crofting staples like potatoes and fodder crops. They are also exploring alternative crops such as flax and hemp for fibers, hops, sweet chestnuts, and both herbal teas and traditional tea.

Case Study – Horticulture production at West Coast Organics

West coast organics is run from a croft in Roag on the North West of Skye. They supply households on Skye with a weekly organic veg box from June to December.

All the produce they supply is grown by hand in their 0.6 Ha organically certified market garden. They have two poly tunnels, and have approximately 1500 m2 outdoor beds and 300 m2 inside beds. Protecting the crops is key. Most outdoor crops have some kind of cover at some point in the growing season. Protection is also provided by extensive hedge planting, that was planted when they started the business in 2015. This provides shelter as well as increasing bio-diversity. Hedges are approximately every ten meters and run East-West in order to provide sufficient shelter from the wind, but this does cause some issues with shade. This year is the first year they have had to trim the hedges, which has provided some wood chip. If they had had more space they would have planted wider shelter belts, which could have provided the opportunity to extract more wood, as short rotation coppice, as well as providing shelter and increased bio-diversity.

They supply approximately 70 local households with veg boxes, that are either collected from the site or from collection points on the island, and have a waiting list. All customer receive the same produce – there is not the option to customise the orders as this would create another level of complexity in the delivery and collection process. They do not target tourists or passing trade, as the permanent residents provide a sufficient market. They now know what they need to grow each year and they have a good degree of certainty. Due to demand if a customer drops out they can be replaced thanks to the waiting list. They do have sufficient flexibility to allow customers to put boxes on hold for short periods if, for example, they are on holiday. They do extensive planning, both of crops and planting. The planting plan maximises growing space, for example under-planting crops such as spring onions and fennel under the tomatoes.

It is possible for this to be profitable. They set their prices roughly based on the costs of organic fresh food sold by somewhere like Waitrose. Non-organic fresh food is so cheap it can be hard to compete but there is a market on Skye that is willing to pay a more realistic price that comes closer to covering the costs of production for fresh organic food. Profit margins could be increased if they were to look at growing more high value crops. They are considering buying in some low value crops, like potatoes, to invest time in higher value crops.

They pack and pick twice a week. At present all planting and harvesting is done by hand, they do have some volunteers and provide training opportunities. They have considered, for example, doing potatoes by machinery but this is not feasible unless they had the facilities to store the crop once it was harvested. They also keep goats and hens, but these are for personal consumption, although the goats do provide manure that is useful for the market garden.

Skills and knowledge

In the past, Eigg had organic vegetable businesses, and many crofters possess valuable knowledge and skills. There is a strong willingness among them to share these skills with new growers. Across Scotland, other producers and communities are also often open to sharing their expertise. Funding is available for site visits to learn from their practices.

Networking organisations such as the Scottish Crofting Federation[30], the Land Workers’ Alliance[31], and the Highland Good Food Partnership[32] offer opportunities to share ideas and skills. They also provide training. The Farm Advisory Service, for example, offers information on horticulture and growing in poly-tunnels[33].

Currently, Scotland does not have a small-scale horticulture course. To boost fruit and vegetable production, the Scottish Government should consider funding such a course, particularly one aimed at supporting small scale, sustainable production.

Site preparation

One challenge on Eigg, and the West Coast of Scotland as a whole, is the weather, particularly the wind. However, with some planning this can be mitigated. West Coast Organics (see case study) have had great success planting windbreaks and shelter belts, which would be a first step. One croft on Eigg has planted hedges to provide shelter for a growing area. Grants are potentially available for planting hedges.

Where soil has not been used for growing, or has had grazing pressure, there may be a need to improve the soil. Knockfarrel Croft (see case study) spent five years improving the soil to get it fully productive, using soil amendments, green manures, crop rotations, and composting to build up the fertility of the soil.

Working together

One option is for individual crofts to develop their own horticultural businesses. For example, West Coast Organics has successfully established a horticultural business on their croft, supplying organic vegetables to customers on Skye.

Alternatively, crofters could grow individually but work toward a collective goal with joint marketing. The Green Bowl (see case study) demonstrates how an online platform can be used to sell a wide variety of goods from different producers. Coordinating crop growing could ensure a steady supply and variety of produce.

A group of crofters might also consider communal growing. This approach allows for shared risks, the cultivation of larger areas, and more effective task-sharing. Such arrangements could be informal or more structured, such as forming a co-operative. SOAS[34] provides guidance on setting up co-operatives.

Many aspects of horticulture are well-suited to communal work. Crofters could share skills, knowledge, seeds, tools, and equipment. Establishing systems for this—whether informal or formal—could help identify and address potential challenges.

Collectively managing facilities, such as processing, drying, storage, or poly-tunnels, is another option. These facilities could be built on an individual croft and shared or rented out, established on the common grazings, or constructed by the community for wider use. There are a number of things to consider, including securing funding, finding suitable land, and working out how to maintain and manage the facilities sustainably.

Communal growing and processing could involve the wider Eigg community. The Green Bowl collaborates with both crofters and non-crofters, all of whom contribute produce for the online store. Many non-crofting Eigg residents have expressed interest in greater access to land for growing. Providing them with secure, long-term access to growing areas would encourage investment of time and energy in creating productive spaces.

There is potentially the opportunity for working more closely with the farms on Eigg. For example, if a ‘veg box’ scheme aims to supply produce for a portion of the year, it might make sense to grow some crops, that are more easily grown at scale, at a farm scale.

A first step might be those on Eigg interested in growing more food to get together to discuss these ideas in more detail.

Funding

Funding is explored in more detail below. While crofters may access grants for capital projects, funding for horticultural is often harder to secure. Current schemes, such as the Basic Payment Scheme and the Less Favoured Area Support Scheme, tend to focus on livestock rather than horticulture.

Land management

Crofters feel a strong responsibility to care for the land. They want to balance the needs of both the crofter and the land, ensuring it remains productive. Crofters have a deep connection to the land, whether they can trace their roots back through generations or have more recent ties. Sustainable land management includes both the sustainable grazing of animals and the planting of trees. The successful development of crofting on Eigg will balance these two priorities to meet the needs of the crofting community as a whole.

Common grazings

Common grazings play a unique role in crofting. (More information about common grazings is found in Appendix 6). In order to be successfully managed there needs to be a grazing committee appointed. This was widely supported and the process of appointing a new committee has begun.

One of the committee’s key tasks will be assessing the future grazing needs of the townships, as this will influence how the grazings are used. Questions to consider include: Do more crofters wish to graze livestock on the common grazings? Do those currently using the grazings plan to continue? Is there interest in communally managing stock?

Grazings and land management

Cattle and sheep are currently grazed on the Cleadale common grazings and due to gaps in the current fencing, sheep from the neighbouring farms are also on the common grazings. There is currently sufficient grazings for the current grazing pressures but there could be opportunities to improve grazings in some areas of both common grazings. There are also opportunities to create pond and wetlands on areas not suitable for grazings.

Fencing and equipment

Making the common grazings stock-proof may be something that the grazing committee want to look at. At present neither of the common grazings are fully stock-proof. Repairs to fencing may not be covered by a grant, unless the existing fencing is in a dilapidated state and is no longer fit for purpose. Agricultural grants may be available for hedges or shelter belts, if their purpose is stock control or protecting stock.

Land survey

Undertaking some kind of formal, or informal, land survey would help identify the areas that are most suitable for grazings, and if there are areas that are less suitable to grazings, such as boggy areas, or areas that are too steep to be safely grazed. It could also provide information about bio-diversity – which will be required for further agricultural funding grants. A survey could also assess the current state of fencing and any stock handling equipment.

Tree planting

Two or more crofters could apply to undertake a tree planting scheme on part of the common grazings, although a plan involving all shareholders may be the most effective way of considering tree planting on the common grazings. Tree planting could include planting shelter belts, planting productive woodlands for coppice or timber, growing fruit trees, extending the current SSSI, planting to get carbon credits or planting for bio-diversity. The Scottish Crofting Federation published a Highland and Island Woodland Handbook, which provides detailed information on woodland creation and management[35]. The Woodland Trust can provide advice and information on what, if any, schemes might be most appropriate for the land.

Access

Currently there are two main access points to the Cleadale common grazings, as well a path over croft land on to the common grazings. Access to the Singing Sands (a popular tourist destination), two scheduled monuments and an area of SSSI is across the common grazings. Concerns were raised that the current access is unsuitable both for visitors and stock.

Creating better access, for crofters, for stock movements, and for visitors as well as for access for any other proposed schemes all need to be considered. Access could also include creating new signage, including some historic information about the sites and features on the common grazings. Access on to the Cuagach common grazings is currently over grown, but the road provides some access. If there is going to be grazing on the Cuagach common grazings, access will need to be improved.

Processing facilities

In the discussions about both livestock and horticulture the potential need for food processing facilities was discussed, whether for the processing of meat, drying and storage of produce, or creating added value products like jams, wines or chutneys. Common grazings land could be used to build such facilities.

Growing facilities

Creating more communal growing space was discussed, either outdoor space to grow crops, fodder and animal bedding communally, or covered growing space such as poly tunnels.

Housing, tourist accommodation, and camping

Whilst it might not be a priority, the lack of housing on Eigg and the potential to generate income from the common grazings, means that the creation of one or more house plots on the common grazings could be considered. Accommodation could also be provided for tourists or volunteers; ranging from an area for wild camping, through to camping facilities or a bunk house to chalets or other holiday accommodation. This could also potentially provide income for the common grazings and the shareholders.

Electricity generation

Many common grazings have some form of renewable energy generation, which as well as generating income for the common grazings, also provides sustainable electricity. A quick initial survey suggests that the common grazings would not be suitable for wind turbines, although it may be possible to explore some solar generation.

Woodlands and trees

Many crofters are interested in growing trees on croft land – either on individual crofts or looking at the opportunities for tree planting on the common grazings.

‘Agroforestry is a new term to some people, but it is a very old practice. People have of course been using trees in agriculture for thousands of years and the history of the UK is full of agroforestry….But it is also ‘new’ because recent years have seen an upsurge in people looking for ways to create more sustainable and nature-friendly farming systems by integrating trees into field crops or pasture systems…interest in agroforestry in the last two years has soared…..This resurgence has been coupled with the ability to learn from examples and farms across Europe and the world, vastly increasing the pool of evidence we can draw on.’

Yields from trees

Growing trees for timber is a possibility. The Trust already manages commercial woodland on Eigg, however it is not clear if growing trees for timber could be viable on the crofting land available.

Fruit and nut trees could contribute to increased food production. Eigg already has a communal orchard that produces apples, and within the group, there is valuable knowledge about what grows well on the island. Similar community or small-scale orchards are now established in other parts of Scotland’s west coast

Willows or other short-rotation coppices could provide material for biomass or wood fuel. Given Eigg’s limited electricity supply, wood burning is likely to remain a key part of the island’s energy mix. Short-rotation coppicing offers a sustainable, low-impact way to produce wood fuel. Willow is also grown on Eigg for basket weaving, and there is potential to expand its cultivation on croft land.

Some crofters have expressed interest in learning how to propagate fruit trees, which could become an additional income stream. The Trust’s tree business, which successfully sells native trees grown from local seeds, could offer opportunities for crofters to supply trees.

Growing trees is also seen as a way to manage land. Trees can provide essential hedging and shelter belts[36] and can be grown on land that would not otherwise be productive, for example wet or boggy areas[37]. Most of the croft land is exposed, which means some small trees may struggle to establish, especially on parts of the common grazings. This could be mitigated by careful planning, or planting ‘nursery’ species to protect trees such as shrubs like broom and gorse or fast-growing trees like alder to protect more slow growing species.

Tree planting can increase bio-diversity. One croft has shown that closely grown copses of native trees can eradicate bracken as well as increased bio-diversity – the increase in birds is particularly striking. A survey could be undertaken to see if the rare, protected hazel woodland at the foot of the cliffs, an area unsuitable for grazing, can be managed, or the area increased[38].

Trees are large plants which carry out photosynthesis – the carbon dioxide extracted from the air can be stored as carbon in the soil and the wood. Planting trees can play a key role in reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere – which is vital if we are to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Advice and support

The Woodland Trust’s Woodland Croft Project[39] offers a free advisory service for crofters interested in planting native trees and managing woodlands. They can provide guidance to individual crofters as well as to grazing committees, helping plan planting schemes on common grazings.

Their advice includes identifying suitable planting areas and tree species, understanding constraints, balancing different land uses (including grazing), and navigating grant applications and other funding opportunities. They also help with understanding relevant regulations. An initial discussion with the Woodland Officer for Eigg was productive, and a visit to the island could be arranged to explore potential schemes. Individual crofters can contact the project for advice at any stage.

The Scottish Crofting Federation Have published two books on small scale woodlands[40]. The Landworkers’ Alliance also offers resources on small-scale forestry projects[41]. Their report, The Promise of Agroforestry[42] , includes case studies that demonstrate how trees can be integrated with farming and food production systems.

Fairer Funding

All of the crofters indicated the need for investment in order to develop their croft, whether to produce more food, develop their business or ensure they had adequate housing. Due to the very low profit margins crofters often are not able to accrue sufficient capital to invest. There is also a lack of available investment. Crofting needs support – many plans cannot happen without investment – but it is not always clear where that investment can come from.

There needs to be an awareness amongst funders that financial support for crofting is not solely about creating new businesses or growing and expanding existing businesses. Crofting needs to be seen through a different lens from the model of continual growth.

For example, if we look at the economy of Eigg, and the crofters in particular, through the lens of Community Wealth Building, we can see why some additional types of support may be needed for small rural businesses. As Scottish Rural Action notes:

“Community wealth building activity serves two functions:

Strengthening community resilience – providing essential services and addressing market failure in areas such as food supply, energy production, transport, care, housing etc.

Market and product innovation – reaching out to new markets and testing new products for local, national and international application.

Enterprises in rural and island areas, including community enterprises and the self-employed, have, through necessity, developed agility to balance both functions. Social enterprises, which draw on diverse investment sources and involve volunteers, are particularly agile. Maintaining this balance is more likely to be a business focus than major profit or workforce expansion. Through this lens, a definition of ‘wealth’ is required which puts emphasis on longer term social and environmental outcomes including sustainability, resilience and wellbeing, rather than on economic growth.[43]”

Crofting plays a key role in the sustaining rural communities, growing low impact, sustainable food production and sensitive land management.

Agricultural funding

There are a wide range of agricultural grants potentially available from the Scottish Government. These are administered by the Rural Payments and Inspections Division (RPID).

Some crofters are able to successfully navigate the complex agricultural funding that is available, however many projects fall through the gaps in funding, or people are put off from applying by the complexity of the system, the lack of clarity around the application process, the need to fund work in advance, or having been previously refused support. There is a perception that the system is so complex that it can only be navigated using the paid services of an advisor, this can be an additional cost, which again puts people off from applying.

It is vital for the economic sustainability of crofting that crofters remain eligible for these grants, and they reflect the real costs crofters face, and recognise the wide-ranging benefits crofting provides. Large scale producers are eligible for ongoing agricultural support – recognising the key role agriculture plays – but small-scale producers face the same administrative bureaucracy for far smaller payments. The administrative burden, both for the crofter and for RPID, often seems disproportionate to the level of support that is provided. In order for crofters to be able to compete with large producers, that often do not provide the same social and environmental benefits as crofters, it is important that, as these schemes are reviewed, the voices of crofters and small producers are heard, and the challenges they face are addressed.

Funding for capital expenditure on, for example, fencing or other improvements is available, but cost have to be paid in advance, and the grants are only paid when work is completed. This can create huge cash flow problems for crofters. In the past grants could be paid up front, or directly to suppliers. The Scottish Government should look at changing the rules, so crofters do not need to pay the costs upfront.

See the Appendix 3 for details of some of the agricultural funding schemes that are available. The Farm Advisor service can provide advice on what funding may be available for any particular crofter via their advice line[44]

Business funding

As well as agricultural payments, croft based businesses may be entitled to business funding. See Appendix 4 for details of some of the grants crofting businesses, either individually or collectively, may be able to access.

The way funding is currently structured, means that in some cases crofting businesses may not be able to access the support they need. Business funding is often limited to either setting up new businesses, or helping businesses grow. As noted above some croft businesses may need different types of support, including ongoing support, to remain viable and deliver their wider social benefits.

Another potential barrier in a requirement that business funding does not overlap with other funding, such as agricultural funding. Of course, it is important to ensure that business are not funded twice for the same thing, however, for example, a crofter wishing to expand into horticulture may fall through the gaps, unable to receive agricultural grants that are aimed at livestock production and unable to get start up grants because the business is already established, and also unable to get other business grants because of a potential overlap with agricultural funding. Whilst this is a hypothetical example, it remains a real risk that crofters will fall through these gaps.

More detailed research should be done to identify gaps in funding, and to understand how the current rules impact crofters. Highlands and Islands Enterprise, The Scottish Government and other funders should look at how they can better support the crofting businesses that play such a key role in both food production and supporting local communities.

Charities

Charitable funding is unlikely to be available to individual crofters, but could potentially provide funding for some projects, that are either done via IEHT or another charitable, or social enterprise.

Funding.Scot[45] is an online database, hosted by SCVO, that provides info on over 1500 grant giving bodies. National Lottery Awards for All Scotland[46] or Community Action Fund[47] could potentially fund projects related to training, knowledge sharing, volunteering or community food growing. Paths For All[48] offer funding for the creating, or development of paths, including the design phase of a project.

Woodland Funding

It is possible to do small scale tree planting for very little cost. Costs can be kept to a minimum by, for example, growing trees from seed. Aside from trees, one of the main costs is protecting the young tree, and in some cases undertaking groundworks such as drainage and mounding. There are no deer on Eigg – protection from which can be costly – but trees may still need protection from other animals such as rabbits and voles. The preparatory work for tree planting, tree planting itself and ongoing maintenance could all be tasks that are suitable for volunteers.

Many of the yields from tree planting take time to accrue, and whilst there may be relatively quick benefits for bio-diversity even willow and short rotation coppice take several years to establish, as do fruit tree, and productive timber can take many decades. This means crofters are unlikely to be able to invest significant amounts in tree planting.

There are a number of funding streams available for the creation and management of woodlands. There are a large number Scottish Forestry funding schemes[49], applications are made via RPID. Most woodland creation schemes include a basic payment, and an ongoing maintenance payment plus potential additional payments for things like protecting trees and fencing. Except for some specific exemptions, grants are paid at a set rate rather than actual costs – which means the grant may not cover the full cost of, for example, woodland creation. Woodland creation schemes may be compatible with other agricultural schemes which could attract agricultural grants, such as Agri-Environment Climate Scheme[50], or hedging for stock control.

Carbon capture and environmental funding

There are now a number of ‘offsetting’ schemes that can provide additional funding for tree planting – and these can potentially cover the gap between grant funding and the actual costs and make financially unviable schemes viable. These schemes are usually paid in addition to any grants that are available for tree planting.

However, these schemes often create ongoing obligations that can run for decades, and schemes require ongoing maintenance and auditing. In the case of crofts these obligations will pass on to future tenants, although it is not yet entirely clear how this will work in practice, and schemes that are planted on common grazings will require co-ordination between the crofters and the owner. At present there is no independent advice available to crofters and farmers to allow informed decisions to be made about which, if any, schemes are most suitable.

Carbon capture schemes are where a landowner, or crofter, is paid to plant trees in the expectation that they will absorb a certain amount of carbon over a given period, often decades, this allows companies that produce carbon to offset the carbon they release. (See Appendix 5 for discussion on the carbon capture schemes and details of some organisations that can fund ‘carbon capture’ projects.)

Grants and charities

There are also a number of charities and grant-giving bodies that can help with the cost of tree planting. Funding.Scot[51] is an online database, hosted by SCVO, that provides information on over 1500 grant giving bodies – some of whom may be able to support tree planting. There are also many schemes that are not included in the database that could be particularly suited to supporting tree planting including: